Using Sender/Receiver for Async Control Flow

Steve Downey

These are the slides, slightly rerendered, from my presentation at C++Now 2023.

Abstract

How can P2300 Senders be composed using sender adapters and sender factories to provide arbitrary program control flow?

- How do I use these things?

- Where can I steal from?

std::execution

Recent version at https://isocpp.org/files/papers/P2300R7.html

A self-contained design for a Standard C++ framework for managing asynchronous execution on generic execution resources.

Three Key Abstractions

Schedulers

Senders

- Receivers

Schedulers

Responsible for scheduling work on execution resources.

Execution resources are things like threads, GPUs, and so on.

Sends work to be done in a place.

Senders

Senders describe work.

Receivers

Receivers are where work terminates.

Value channel

Error channel

- Stopped channel

Work can terminate in three different ways.

- Return a value.

- Throw an exception

- Be canceled

It's been a few minutes. Lets see some simple code.

Hello Async World

1: 2: #include <stdexec/execution.hpp> 3: #include <exec/static_thread_pool.hpp> 4: #include <iostream> 5: 6: int main() { 7: exec::static_thread_pool pool(8); 8: 9: stdexec::scheduler auto sch = pool.get_scheduler(); 10: 11: stdexec::sender auto begin = stdexec::schedule(sch); 12: stdexec::sender auto hi = stdexec::then(begin, [] { 13: std::cout << "Hello world! Have an int.\n"; 14: return 13; 15: }); 16: 17: auto add_42 = stdexec::then(hi, [](int arg) { return arg + 42; }); 18: 19: auto [i] = stdexec::sync_wait(add_42).value(); 20: 21: std::cout << "The int is " << i << '\n'; 22: 23: return 0; 24: } 25:

Hello Async World Results

Hello world! Have an int. The int is 55

When All - Concurent Async

1: exec::static_thread_pool pool(3); 2: 3: auto sched = pool.get_scheduler(); 4: 5: auto fun = [](int i) { return i * i; }; 6: 7: auto work = stdexec::when_all( 8: stdexec::on(sched, stdexec::just(0) | stdexec::then(fun)), 9: stdexec::on(sched, stdexec::just(1) | stdexec::then(fun)), 10: stdexec::on(sched, stdexec::just(2) | stdexec::then(fun))); 11: 12: auto [i, j, k] = stdexec::sync_wait(std::move(work)).value(); 13: 14: std::printf("%d %d %d\n", i, j, k);

Describe some work:

Creates 3 sender pipelines that are executed concurrently by passing to `when_all`

Each sender is scheduled on `sched` using `on` and starts with `just(n)` that creates a Sender that just forwards `n` to the next sender.

After `just(n)`, we chain `then(fun)` which invokes `fun` using the value provided from `just()`

Note: No work actually happens here. Everything is lazy and `work` is just an object that statically represents the work to later be executed

When All - Concurent Async - Results

0 1 4

Order of execution is by chance, order of results is determined.

Dynamic Choice of Sender

1: exec::static_thread_pool pool(3); 2: 3: auto sched = pool.get_scheduler(); 4: 5: auto fun = [](int i) -> stdexec::sender auto { 6: using namespace std::string_literals; 7: if ((i % 2) == 0) { 8: return stdexec::just("even"s); 9: } else { 10: return stdexec::just("odd"s); 11: } 12: }; 13: 14: auto work = stdexec::when_all( 15: stdexec::on(sched, stdexec::just(0) | stdexec::let_value(fun)), 16: stdexec::on(sched, stdexec::just(1) | stdexec::let_value(fun)), 17: stdexec::on(sched, stdexec::just(2) | stdexec::let_value(fun))); 18: 19: auto [i, j, k] = stdexec::sync_wait(std::move(work)).value(); 20: 21: std::printf("%s %s %s", i.c_str(), j.c_str(), k.c_str());

Enough API to talk about control flow

The minimal set being:

- stdexec::on

- stdexec::just

- stdexec::then

- stdexec::let_value

- stdexec::sync_wait

I will mostly ignore the error and stop channels

Vigorous Handwaving

Some Theory

Continuation Passing Style

Not At All New

Pass a "Continuation"

Where to go next rather than return the value.

add :: Float -> Float -> Float add a b = a + b add_cps :: Float -> Float -> (Float -> a) -> a add_cps a b cont = cont (a + b)

auto add(float a, float b) -> float { return a + b; } template<typename Cont> auto add_cps(float a, float b, Cont k) { return k(a+b); }

Inherently a tail call

In continuation passing style we never return.

We send a value to the rest of the program.

Hard to express in C++.

Extra machinery necessary to do the plumbing.

Also, some risk, so we don't always do TCO.

We keep the sender "thunks" live so we don't dangle references.

Intermittently Popular as a Compiler Technique

The transformations of direct functions to CPS are mechanical.

The result is easier to optimize and mechanically reason about.

Equivalent to Single Static Assignment.

Structured Programming can be converted to CPS.

Delimted Continuations

General continuations reified as a function.

Everyone knows that when a process executes a system call like ‘read’, it gets suspended. When the disk delivers the data, the process is resumed. That suspension of a process is its continuation. It is delimited: it is not the check-point of the whole OS, it is the check-point of a process only, from the invocation of main() up to the point main() returns. Normally these suspensions are resumed only once, but can be zero times (exit) or twice (fork).

Oleg Kiselyov Fest2008-talk-notes.pdf

If this qoute reminds you of coroutines, you are paying attention.

Haskell's Cont Type

newtype Cont r a = Cont { runCont :: (a -> r) -> r }

This is roughly equivalent to the sender value channel. A Cont takes a reciever, a function that consumes the value being sent, and produces an r, the result type.

The identity function is often used.

Underlies std::execution

The plumbing is hidden.

Senders "send" to their continuations, delimted by the Reciever.

Another Level of Indirection

Solves all problems

Adds two more.

At least

CPS Indirects Function Return

Transform a function

$latex A \rightarrow B $

to

$latex A \rightarrow B \rightarrow ( B \rightarrow R ) \rightarrow R $

add :: Float -> Float -> Float add a b = a + b add_cps :: Float -> Float -> (Float -> A) -> A add_cps a b cont = cont (a + b)

Sender Closes Over A

$latex B \rightarrow ( B \rightarrow R ) \rightarrow R $

The $LATEX A$ is (mostly) erased from the Sender.

Reciever Is The Transform to Result

$latex ( B \rightarrow R ) \rightarrow R $

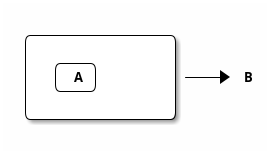

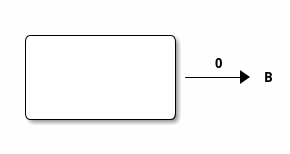

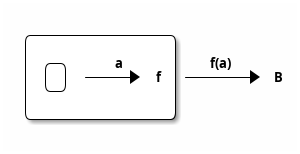

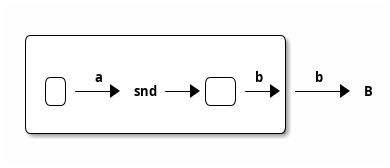

Some Pictures

Sender

just

stdexec::just(0)

then

auto f(A a) -> B; auto s = stdexec::just(a) | stdexec::then(f);

let_value

sender_of<set_value_t(B)> auto snd(A a); auto s = stdexec::just(a) | stdexec::let_value(snd);

In which we use the M word

Sender is a Monad

(surprise)

(shock, dismay)

Function Composition is the hint

Functions are units of work.

We compose them into programs.

The question is if the rules apply.

Monadic Interface

- bind or and_then

$latex M \langle a \rangle \rightarrow (a \rightarrow M \langle b \rangle ) \rightarrow M \langle b \rangle $

- fish or kleisli arrow

$latex (a \rightarrow M \langle b \rangle ) \rightarrow (b \rightarrow M \langle c \rangle ) \rightarrow (a \rightarrow M \langle c \rangle ) $

- join or flatten or mconcat

$latex M \langle M \langle a \rangle \rangle \rightarrow M \langle a \rangle $

Monad Interface

Applicative and Functor parts

- make or pure or return

$latex a \rightarrow M \langle a \rangle $

- fmap or transform

$latex (a \rightarrow b) \rightarrow M \langle a \rangle \rightarrow M \langle b \rangle $

Any one of the first three and one of the second two can define the other three

Monad Interface

Monad Laws

- left identity

- bind(pure(a), h) == h(a)

- right identity

- bind(m, pure) == m

- associativity

- bind(bind(m, g), h) == bind(m, bind((\x -> g(x), h))

Monad Laws

Sender is Three Monads in a Trench-coat

Stacked up.

- Value

- Error

- Stopped

The three channels can be crossed, mixed, and remixed. Focus on the value channel for simplicity.

The Three Monadic Parts

just

Send a value.

pure

just lifts a value into the monad

then

Send a value returned from a function that takes its argument from a Sender.

fmap or transform

then is the functor fmap

let_value

Send what is returned by a Sender returned from a function that takes its argument from a Sender.

bind

let value is the monadic bind

Necessary and Sufficient

The monadic bind gives us the runtime choices we need.

Basis of Control

- Sequence

- Decision

- Recursion

Sequence

1: stdexec::sender auto work = 2: stdexec::schedule(sch) 3: | stdexec::then([] { 4: std::cout << "Hello world! Have an int."; 5: return 13; 6: }) 7: | stdexec::then([](int arg) { return arg + 42; }); 8: 9: auto [i] = stdexec::sync_wait(work).value(); 10:

One thing after another.

Decision

1: exec::static_thread_pool pool(8); 2: 3: stdexec::scheduler auto sch = pool.get_scheduler(); 4: 5: stdexec::sender auto begin = stdexec::schedule(sch); 6: stdexec::sender auto seven = stdexec::just(7); 7: stdexec::sender auto eleven = stdexec::just(11); 8: 9: stdexec::sender auto branch = 10: begin 11: | stdexec::then([]() { return std::make_tuple(5, 4); }) 12: | stdexec::let_value( 13: [=](auto tpl) { 14: auto const& [i, j] = tpl; 15: 16: return tst((i > j), 17: seven | stdexec::then([&](int k) noexcept { 18: std::cout << "true branch " << k << '\n'; 19: }), 20: eleven | stdexec::then([&](int k) noexcept { 21: std::cout << "false branch " << k << '\n'; 22: })); 23: }); 24: 25: stdexec::sync_wait(std::move(branch));

true branch 7

Control what sender is sent at rentime depending on the state of the program when the work is executing rather than in the structure of the senders.

tst function

1: inline auto tst = [](bool cond, 2: stdexec::sender auto left, 3: stdexec::sender auto right) 4: -> exec::variant_sender<decltype(left), 5: decltype(right)> { 6: if (cond) 7: return left; 8: else 9: return right; 10: }; 11:

Recursion

Simple Recursion

1: 2: using any_int_sender = 3: any_sender_of<stdexec::set_value_t(int), 4: stdexec::set_stopped_t(), 5: stdexec::set_error_t(std::exception_ptr)>; 6: 7: auto fac(int n) -> any_int_sender { 8: std::cout << "factorial of " << n << "\n"; 9: if (n == 0) 10: return stdexec::just(1); 11: 12: return stdexec::just(n - 1) 13: | stdexec::let_value([](int k) { return fac(k); }) 14: | stdexec::then([n](int k) { return k * n; }); 15: } 16:

1: 2: int k = 10; 3: stdexec::sender auto factorial = 4: begin 5: | stdexec::then([=]() { return k; }) 6: | stdexec::let_value([](int k) { return fac(k); }); 7: 8: std::cout << "factorial built\n\n"; 9: 10: auto [i] = stdexec::sync_wait(std::move(factorial)).value(); 11: std::cout << "factorial " << k << " = " << i << '\n'; 12:

factorial built factorial of 10 factorial of 9 factorial of 8 factorial of 7 factorial of 6 factorial of 5 factorial of 4 factorial of 3 factorial of 2 factorial of 1 factorial of 0 factorial 10 = 3628800

General Recursion

1: auto fib(int n) -> any_int_sender { 2: if (n == 0) 3: return stdexec::on(getDefaultScheduler(), stdexec::just(0)); 4: 5: if (n == 1) 6: return stdexec::on(getDefaultScheduler(), stdexec::just(1)); 7: 8: auto work = stdexec::when_all( 9: stdexec::on(getDefaultScheduler(), stdexec::just(n - 1)) | 10: stdexec::let_value([](int k) { return fib(k); }), 11: stdexec::on(getDefaultScheduler(), stdexec::just(n - 2)) | 12: stdexec::let_value([](int k) { return fib(k); })) | 13: stdexec::then([](auto i, auto j) { return i + j; }); 14: 15: return work; 16: } 17:

1: 2: int k = 30; 3: stdexec::sender auto fibonacci = 4: begin | stdexec::then([=]() { return k; }) | 5: stdexec::let_value([](int k) { return fib(k); }); 6: 7: std::cout << "fibonacci built\n"; 8: 9: auto [i] = stdexec::sync_wait(std::move(fibonacci)).value(); 10: std::cout << "fibonacci " << k << " = " << i << '\n';

fibonacci built fibonacci 30 = 832040 fibonacci 30 = 832040

Fold

1: 2: if (first == last) { 3: return stdexec::just(U{std::move(init)}); 4: } 5: 6: auto nxt = 7: stdexec::just(std::invoke(f, std::move(init), *first)) | 8: stdexec::let_value([this, 9: first = first, 10: last = last, 11: f = f 12: ](U u) { 13: I i = first; 14: return (*this)(++i, last, u, f); 15: }); 16: return std::move(nxt);

1: 2: auto v = std::ranges::iota_view{1, 10'000}; 3: 4: stdexec::sender auto work = 5: begin 6: | stdexec::let_value([i = std::ranges::begin(v), 7: s = std::ranges::end(v)]() { 8: return fold_left(i, s, 0, [](int i, int j) { return i + j; }); 9: }); 10: 11: auto [i] = stdexec::sync_wait(std::move(work)).value(); 12:

work = 49995000

Backtrack

using any_node_sender = any_sender_of<stdexec::set_value_t(tree::NodePtr<int>), stdexec::set_stopped_t(), stdexec::set_error_t(std::exception_ptr)>; auto search_tree(auto test, tree::NodePtr<int> tree, stdexec::scheduler auto sch, any_node_sender&& fail) -> any_node_sender { if (tree == nullptr) { return std::move(fail); } if (test(tree)) { return stdexec::just(tree); } return stdexec::on(sch, stdexec::just()) | stdexec::let_value([=, fail = std::move(fail)]() mutable { return search_tree( test, tree->left(), sch, stdexec::on(sch, stdexec::just()) | stdexec::let_value( [=, fail = std::move(fail)]() mutable { return search_tree( test, tree->right(), sch, std::move(fail)); })); }); return fail; }

tree::NodePtr<int> t; for (auto i : std::ranges::views::iota(1, 10'000)) { tree::Tree<int>::insert(i, t); } auto test = [](tree::NodePtr<int> t) -> bool { return t ? t->data() == 500 : false; }; auto fail = begin | stdexec::then([]() { return tree::NodePtr<int>{}; }); stdexec::sender auto work = begin | stdexec::let_value([=]() { return search_tree(test, t, sch, std::move(fail)); }); auto [n] = stdexec::sync_wait(std::move(work)).value(); std::cout << "work " << " = " << n->data() << '\n';

work = 500

Don't Do That

Can is not Should

Write an Algorithm

Why You Might

- Throughput

- Interruptable

Thank You